Senior Partner

April 2021

Investing is a never-ending struggle between worry and optimism. The past 14 months illustrated that better than any period in recent memory. Beginning with panicked selling set off by the pandemic, the period ended with stock market indices sharply higher and many high-promise-but-no-earnings stocks reaching bubble-like valuations. So in a year in which the U.S. economy is projected to grow at its fastest rate in decades and corporate earnings are expected to increase by double-digit rates, it should come as no surprise that investors have found new reasons to worry. And the most prominent reason of late is rising prices, otherwise known as inflation.

Understanding why many investors are beginning to worry about inflation requires a review of the policy measures used to combat the negative financial effects of this past year’s pandemic. At the pandemic’s beginning, policymakers viewed deflation, not inflation, as a major threat. The sudden sharp drop in consumer and business spending combined with falling financial markets threatened not only to push the economy into depression, but also to begin a period of deflation, or falling prices. Deflation is generally viewed more negatively than inflation—at least moderate inflation— because it makes meeting debt obligations more difficult and it incents people to delay spending in anticipation of falling prices.

The U.S. government used both monetary and fiscal measures to battle the deflation threat and reflate the economy. On the monetary side, the Federal Reserve created huge sums of new money while lowering interest rates both to encourage borrowing and to discourage leaving money in savings. On the fiscal side, Congress provided people with direct stimulus checks to replace lost wages or, for those still employed, boost spending and investment. And it worked!

But here is where inflation concerns come into the picture. Policymakers have decided that if one large dose of medicine was good for the patient, then more large doses will be even better. So in December and March, Congress passed two more large spending bills, dropping a combined $2.8 trillion into the economy at a time when, thanks to vaccines and an easing of restrictions on businesses, it was already on a path to recovery. That $2.8 trillion, equal to 13% of the U.S. economy’s annual production, is in response to a much smaller 2.4% economic decline in 2020. And where does this money come from? It comes from more debt and more money printing, thereby stoking inflation fears.

Federal Reserve Chairman Jerome Powell has said that this additional stimulus and money printing, along with near-zero short-term interest rates, are necessary because we are still in the reflation phase of the recovery. He further noted that any inflation it may cause is transitory. In fact, the Federal Reserve raised its longstanding 2% inflation target to a level moderately above 2% for an extended time to offset the prior period of lower inflation.

Whether Chairman Powell is correct comes down to the economic basics of supply and demand. On one side, we have a historic increase in money supply coupled with massive government spending reaching the economy just as it is about to fully reopen. (Think demand.) On the other side, the economy still has tremendous amounts of unused capacity, with sales at restaurants, hotels, and other businesses still well below pre-pandemic levels. (Think supply.) How the two balance out will determine where inflation goes from here.

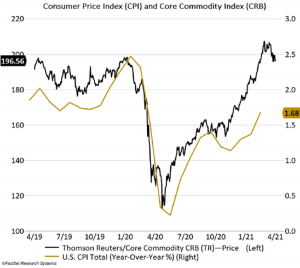

Unfortunately, the coming months’ inflation reports will only muddy the picture. This is because, as shown in Chart 1, the Consumer Price Index (CPI), a widely followed measure of inflation, is strongly correlated to commodity prices. Commodity prices fell sharply during last year’s first four months only to recover in the months that followed. This is a good example of deflation followed by reflation. However, as year-over- year changes in the CPI are reported going forward, the numbers will soon no longer include last year’s early drop in prices, but instead will include only the reflation period that followed, thereby causing the CPI to rise. This may cause casual observers to believe that we are experiencing a spike in inflation rather than reflating from the prior drop in prices.

CHAR T 1

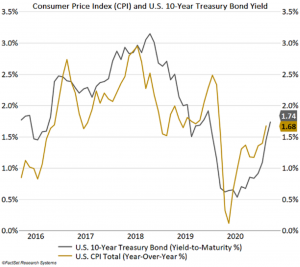

In addition to the challenges that inflation causes for consumers, it also affects both bond and stock prices. Yields on longer-maturity bonds fluctuate with changes to the inflation rate, as shown in Chart 2, which compares the yield for the 10-year U.S. Treasury bond to the Consumer Price Index (CPI). When inflation has risen, so have the yields on longer-maturity bonds. And because valuations for stocks generally move inversely with longer-maturity bond yields, a rise in yields can mean lower stock valuations. Therefore, it will be important for investors to monitor future changes in inflation whether they are worried or optimistic.

CHAR T 2

DISCLAIMER: The information provided in this material should not be considered as a recommendation to buy, sell or hold any particular security. This report includes candid statements and observations regarding investment strategies, individual securities, and economic and market conditions; however, there is no guarantee that these statements, opinions, or forecasts will prove to be correct. Actual results may differ materially from those we anticipate. The views and strategies described in the piece may not be suitable to all readers and are subject to change without notice. You should not place undue reliance on forward-looking statements, which are current as of the date of this report. The information is not intended to provide and should not be relied on for accounting, legal, and tax advice or investment recommendations. Investing in stocks involves risk, including loss of principal. Past performance is not a guarantee of future results.