J. Andrew Concannon

CFA, CFP®

Senior Partner

Senior Partner

July 2020

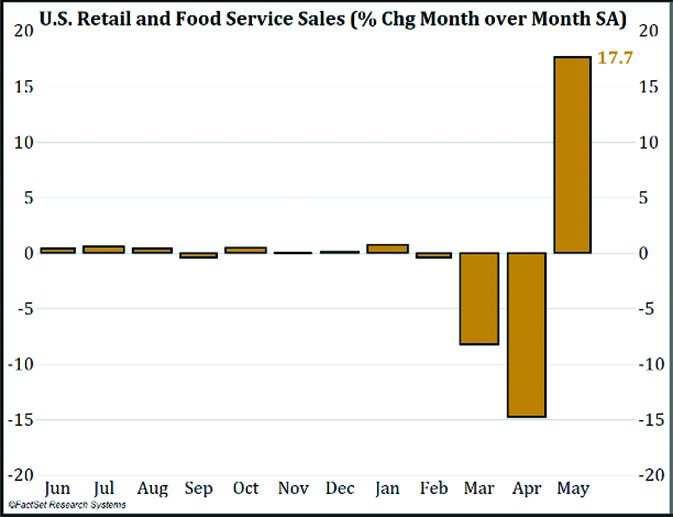

We’ll start with good news: the recession that began in February has already ended. That is not to say that the economy is back to where it was in January. It is far from it. But, according to the National Bureau of Economic Research (the official arbiter for defining U.S. recession periods), a recession is a period of diminishing rather than diminished activity. And as states began easing lockdown restrictions, economic activity was no longer diminishing, but rather expanding. For example, see May’s record monthly increase in retail sales as shown in the chart below. Thus, the steepest recession since the Great Depression appears to have ended after just three months, although it will be much longer before the economy is fully mended.

Understanding how the recent recession could end so soon requires distinguishing its cause from factors that preceded typical recessions during the past century. Those downturns, lasting 11 months on average, were usually caused by some combination of an overheated economy, high debt levels, and rising interest rates.1By contrast, this recession was caused by a natural disaster in the form of a virus. Or more precisely, it was caused by governments locking down businesses to slow the virus’s spread. Those lockdowns caused immediate disruptions and distortions to economic activity—not unlike the effects caused by natural disasters such as hurricanes and earthquakes. But this pandemic’s vast reach and duration made it far worse economically than most natural disasters. Rather than affecting only a city or state, it has affected nearly the entire world, and continues to do so. Natural disasters, such as hurricanes, cause a sudden decline in economic activity followed by a sharp rebound as destroyed items are replaced. The pandemic, as this one is being managed, started with a sudden decline followed by a sharp government stimulus-supported rebound as businesses have been allowed to reopen. The economy’s ability to bounce back depends on several factors including the containment of the virus, government support to individuals, businesses, and financial markets, and the duration of lockdown restrictions. Of these, the duration of the lockdown restrictions is the most important for the economy. No government support program can substitute for an open, fully functioning economy. In March, one of the most concerning unknowns was how long the lockdowns would last. As it turned out, the duration was at the short end of the expected range. Therefore, the economic damage, although extensive, was less than it would have been had the lockdowns been extended for a much longer period.

Bond markets experienced severe imbalances in March causing U.S. Treasury bond yields to plunge to record lows and corporate and municipal bond yields to rise sharply. To calm the markets, the Federal Reserve swiftly announced massive bond-purchase programs and other forms of support. Even before the implementation of those programs, yields on corporate and municipal bonds fell quickly. The Federal Reserve also pushed short-term interest rates back near zero as it had done during the 2008–2009 financial crisis. Lower bond yields mean lower returns going forward. Although short-to-intermediate-term investment-grade bonds still offer important qualities of liquidity and limited volatility, current yield levels will not meet most investors’ return goals. And the Federal Reserve’s announced plan to hold short-term interest rates near zero through 2022 means yields will likely remain low for an extended period. Low bond yields make finding value a relative game. We currently view below-investment-grade corporate bonds to be attractive due to historically high yields relative to U.S. Treasury bonds. We also see value in municipal and agency bonds for the same reason, although absolute yields are less compelling.

Since February’s peak, the U.S. stock market has experienced both the fastest decline from an all-time high (-33.9% in 23 trading days) and the largest 50-day increase (+39.6%).2The stock market has historically served as a leading indicator of economic activity, and this time seems no different. But never has it moved with greater speed or volatility. Nor have there been many instances when the returns between different stock groups have varied so widely, with many larger, more stable companies having fared well while small and cyclical company stocks took the brunt of the decline. Some investors have expressed concern that stock prices have rebounded too fast and too far for this stage of the economic recovery. We agree that the stock market, when viewed as a whole, appears richly priced on traditional measures such as price relative to earnings. However, much of the market’s high valuation premium is concentrated across the largest companies that make up an oversized portion of widely followed market indices. By contrast, the stocks of many smaller and cyclical companies are not expensive, thereby leaving opportunities for investors. Stock prices have historically moved in the direction of future earnings with interest rates influencing valuation levels. Earnings should begin to improve with the economy’s reopening, which explains the stock market’s rebound. But as always, longer-term earnings growth is less knowable. What is known, however, is the Federal Reserve’s plan to hold short-term interest rates near zero through 2022. Unable to meet return goals with cash equivalents and bonds, investors will seek higher returns in risk assets including stocks. Therefore, we may be in for a period of elevated stock valuations regardless of earnings growth.

1The median recession period during the Fed era (since 1913) has been 11 months. Source: Merk Investments, Bloomberg.

2Price-only returns for the Standard & Poor’s 500® Index. Fastest decline measured from the closing price on February 19, 2020 to the closing price on March 23, 2020. The largest 50-day increase measured from the closing price on March 23, 2020 to the closing price on June 3, 2020