Gavin W. Stephens

CFA

Chief Investment Officer

Chief Investment Officer

October 2021

“I used to think if there was reincarnation, I wanted to come back as the president or the pope or a .400 baseball hitter. But now I want to come back as the bond market. You can intimidate everybody.”

—James Carville, political consultant, 1993

Nearly 30 years ago, bond investors were considered a powerful lot—powerful enough to earn the moniker “bond vigilantes.” Responding to deficit-fueled government spending, these investors would sell government bonds and thereby raise interest rates and the government’s cost of borrowing. Their perceived influence could strike fear into policy makers and politicians alike.

Today’s world feels much different. With the major economies operating with increasing budget deficits—and carrying historically high and growing levels of debt—interest rates are stuck near all-time lows. In this seemingly untenable situation, one wonders, “Where are the vigilantes?” One answer: the vigilantes are now skeptics.

By several indicators, the bond market appears to make little sense. Consider long-term U.S. Treasury bond yields, for example, which are traditionally composed of two elements: expectations of future interest rates and compensation for inflation. The latter factor has played the most influential role in determining the level of long-term interest rates.

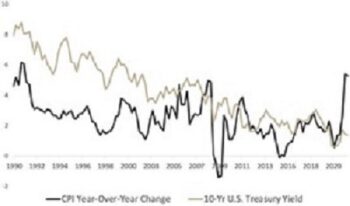

The historical relationship between inflation and interest rates appears broken. As the chart at right shows, the 10-year Treasury bond yield has closely tracked the Consumer Price Index (CPI), with yields nearly always above that of the index.

Today, however, the CPI has measured inflation at nearly 5.3%, higher than any period since 2008. Rather than adjusting to compensate investors for inflation, the 10-year Treasury bond’s yield sits at just 1.4%, resulting in a negative real return of about -3.9%.1

CHART 1

INFLATION RATES AND U.S. TREASURY YIELDS

This bond-market madness has also spread beyond Treasury bonds: even U.S. high-yield corporate bonds, with a yield just under 4%, offer no income over inflation. Simply put, interest rates are not “where they ought to be.”2

Speculators may abound in the capital markets, but the U.S. government-bond market is generally not their preferred habitat. While we can shake our heads at this bond-market madness, prudence suggests that we pause and ask what the vigilantes are saying. On closer examination, it appears that the vigilantes have become skeptics—skeptical both that high inflation will persist and that high debt will improve economic growth.

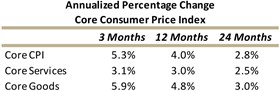

As the table below shows, this summer’s high CPI readings look quite different when we expand the period to include the deflation that occurred at the start of the pandemic.3

This table illustrates that price levels have accelerated more rapidly over recent months; however, when compared to price levels from 2019, prices of core goods and services have increased at a more measured annual rate of about 2.8%. While higher than the Federal Reserve’s target rate of 2.0%, this longer-term inflation rate is about half of what we’ve seen in recent CPI reports, reports that are undoubtedly influenced by supply-chain bottlenecks. As we mentioned in our April Insights, this surge in inflation might be better understood as reflation from last year’s drop in consumer prices. With bond yields failing to adjust to these higher recent readings, bond investors are betting that reflation will end, and longer-term inflation trends will resume.

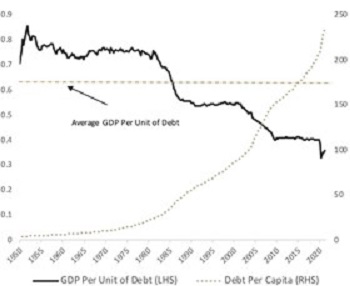

The bond market also appears skeptical that higher debt will provide a meaningful jolt to economic growth. Growing U.S. fiscal deficits, combined with multiple rounds of monetary stimulus, have driven debt to higher levels. As Chart 2 shows, these higher debt levels have produced diminishing levels of economic growth. Since 1950, each incremental dollar of public debt has produced, on average, about $0.60 of economic output. The productivity of debt has trended downward over the past 20 years and now sits at nearly half of its long-term average.4

CHART 2

U.S. GROSS DOMESTIC PRODUCT PER UNIT OF DEBT

While various rounds of monetary stimulus have kept interest rates low and injected vast amounts of cash into the financial system, these efforts have been less successful in producing economic growth.5

On closer view, perhaps the vigilantes haven’t disappeared, and perhaps the bond market is more rationale than it seems. We are not suggesting that interest rates won’t occasionally rise; rates will adjust as economic cycles change. However, if the bond skeptics are correct, interest rates will ultimately struggle to return to where “they ought to be” and will stay low for a long time.

1Bloomberg, as of September 17, 2021.

2As of September 21, 2021, the yield to worst of the Bloomberg U.S. Corporate High Yield Index was 3.89%.

3Bloomberg, as of September 14, 2021. Annualized percentage change in core CPI from periods beginning August 31, 2019, August 31, 2020, and May 31, 2021 to the period ending August 31, 2021.

4Bloomberg. Total debt is defined as U.S. non-financial debt, which includes government, business, and household obligations. Data as of June 30, 2021.

5To further illustrate this challenge, consider the diminishing contribution of productive debt entering the economy, namely loans negotiated between banks and small businesses. Over the last decade, commercial banks’ collective loan-to-deposit ratio has declined by almost 50%. Bloomberg, as of September 17, 2021.

DISCLAIMER: The information provided in this material should not be considered as a recommendation to buy, sell, or hold any particular security. This report includes candid statements and observations regarding investment strategies, individual securities, and economic and market conditions; however, there is no guarantee that these statements, opinions, or forecasts will prove to be correct. Actual results may differ materially from those we anticipate. The views and strategies described in the piece may not be suitable to all readers and are subject to change without notice. You should not place undue reliance on forward-looking statements, which are current as of the date of this report. The information is not intended to provide and should not be relied on for accounting, legal, and tax advice or investment recommendations. Investing in stocks involves risk, including loss of principal. Past performance is not a guarantee of future results.